Yeah, like I'm going to write a comprehensive overview of Miles Davis' legacy in a blog post. The guy went through so many phases that you could write a whole book on any one of those periods (recommended: Phil Freeman's

Running The Voodoo Down on Miles's electric period). So I'm going to stick to a few words about the albums I have, thanks. I do want to mention how much I like, as a non-horn player, that Miles played the trumpet, the brassiest and most declarative of popular horns. Where saxophones and sax players tend to expound in million-note expressions, being the Modernists of horn players, Miles used the trumpet for short bursts of profundity like a Zen master of jazz. Dizzy Gillespie is the only other major trumpet player I can think of, and Dizzy tended to go for longer note-flurries. But Dizzy also left a lot of room in his sound, and Miles expanded that same sense of space to incredible effect. Miles was also a genius at assembling sidemen. To most effectively play the part of cool, removed Zen master, he needed a band around him that would generate incredible heat and light, and he almost always achieved that.

Birth of the Cool (recorded 1949-1950, released 1956). A collection of early sides that Davis released that happened to create the paradigm for the original West Coast gangstas of cool jazz. Unlike most cool jazz dudes, Davis wasn't white, but like most cool jazz dudes, Davis was classically trained and he liked heroin.

Bags' Groove (recorded 1954, released 1957) and

Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (recorded 1954 and 1956, released 1958). These albums share tracks from a session where Miles included Thelonious Monk on piano. The problem with having two worldchanging talents in the same room is that immense talents are usually attached to immense egos, and the two men apparently did not get along well. There was a rumor that they came to blows during the session, but Miles explained later to one of his biographers that these rumors were ridiculous because Monk was a much larger man than Miles, and Miles would never fight a guy who was sure to beat his ass. The results are pretty tasty, though. On

Bags' Groove, only the title track was from this session, which also included Milt "Bags" Jackson on vibraphone. On the

Modern Jazz Giants, all of the tracks except, ironically, Monk's "'Round Midnight" are from that session. The rest of

Bags' Groove is from an earlier session from 1954 with Sonny Rollins on sax. The other track on

Modern Jazz Giants is from a 1956 session with Coltrane on sax and the Red Garland Trio rounding out what jazz historians call Miles' first great quintet. I hope the roster is enough to indicate that these albums are quite good.

Miles: The New Miles Davis Quintet (recorded 1955, released 1956),

'Round About Midnight (recorded 1955 and 1956, released 1957),

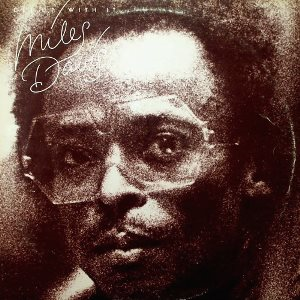

Cookin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (recorded 1956, rel. 1957),

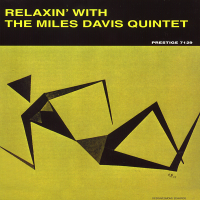

Relaxin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (recorded 1956, rel. 1958),

Workin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (recorded 1956, rel. 1959),

Steamin' With The Miles Davis Quintet (recorded 1956, rel. 1961). These are the albums by Miles's first great quintet (Miles, Coltrane on sax, Red Garland on piano, Philly Joe Jones on drums, Paul Chambers on bass). Coltrane's first albums as a bandleader are with this same group

sans Miles. If you like hard bop, this is where it is at, the best example of the form. The

New Miles Davis Quintet album is the weakest of these, but it's far from weak. The rest are extraordinary, although their punch has been a little dimmed by the fact that they are so well-known. Start with

Relaxin', which is my favorite.

Miles And Monk At Newport (1958). This is half of an album that features Miles' 1958 band on one side and Monk's contemporary band on the other. The musicians didn't play together, and each half has been expanded and released as its own album. I don't have either, though.

Milestones (1958),

Kind Of Blue (1959), and

Someday My Prince Will Come (1961). If you are a fan of jazz, you probably own a copy of

Kind Of Blue. If you do not, you should remedy this immediately. On these two albums, Miles was opening up a modal model for jazz that more or less revolutionized that way that musicians could improvise in music by getting rid of the extensive chord changes of hard bop. Although Coltrane left his quintet for two years after the recording of the first great quintet albums, he rejoined the band for

Milestones, which features said quintet plus Cannonball Adderley on alto sax.

Milestones is fantastic, but on

Kind Of Blue, Miles' band rip open the songs in a completely new way. The

Kind Of Blue band has Jimmy Cobb on drums instead of Philly Joe Jones and Bill Evans and Wynton Kelly alternating on piano, but otherwise is the same as on

Milestones. It's one of the best examples of recorded music that there is, and that's not hyperbole.

Someday My Prince Will Come is a continuation of these ideas with mostly the same band (although Hank Mobley joins Coltrane on one track and replaces Coltrane and Adderley on most of the others). It's a great album, too.

Porgy And Bess (1958) and

Sketches of Spain (1960). The composer and bandleader Gil Evans contributed quite a bit to Miles' modality, although these are easily some of his most accessible albums for people who aren't fans of jazz. Sweeping orchestrated arrangements dominate both albums, and some purists argue that it isn't jazz. Get used to that idea because it will come up again and again over Miles' career.

Seven Steps To Heaven (1963) and

Live In Japan 1964. These albums don't have much in common, but they're both transitional.

Seven Steps features much of what would be Miles' second great quintet.

Live In Japan is a bootleg from Miles's tour with the great Sam Rivers on sax, the only time they would play together. Both are killer on their own terms and a glimpse of the greatness that was about to erupt.

E.S.P. (1965),

Complete Live At The Plugged Nickel 1965,

Miles Smiles (1967),

Sorcerer (1967),

Antwerp Blues October 28 1967, and

Nefertiti (1968). These are the albums by Miles' second great quintet, which featured Miles on trumpet, Wayne Shorter on sax, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums. It's significant that Miles' first great quintet did not play together very long, and in fact, most of their recordings were made over the course of a few days and consisted of standards and songs by other writers. The second quintet was together for a number of years and most of their work was written by members of the quintet. They were, in a real way, a band like few others in jazz, but quite close to the more democratic and committed concept of a rock band.

E.S.P. is a fitting title to their first album together, because the members appeared to share a single mind and purpose. The

Plugged Nickel box is a recording of two nights in December 1965 that features the quintet knocking out standards and older Miles tunes.

Miles Smiles, recorded late in 1966, shows how well the rhythm section was meshing with the horn players. Like all of these, really, it's a barnburner.

Antwerp Blues is a bootleg and it cooks.

Sorcerer and

Nefertiti are the best of these, though, with the quintet firing on all cylinders (minus the tacked-on track with singer Bob Dorough [of Schoolhouse Rock fame] from 1962 at the end of

Sorcerer). These albums are perhaps the finest example of a hard bop quintet looking to break through to something new, and they left Miles with nowhere to go but outside of the realms of what people had hereto considered jazz.

Miles In The Sky (1968),

Water Babies (recorded 1967-1968, released 1975),

Filles de Kilimanjaro (1969), and

Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, 1965-1968. This is the sound of the quintet in transition.

Miles In The Sky has Hancock playing electric piano and Carter on electric bass for one track, along with George Benson's electric guitar on another.

Water Babies, which wasn't released for almost a decade, has the classic second great quintet on three tracks and the

In A Silent Way variation on three. It's decent material, but not as great as the studio releases of the time.

Filles de Kilimanjaro has the electricified quintet on three tracks, but replaced Hancock with Chick Corea and Carter with Dave Holland on two tracks. Notable: the Wikipedia page says that Stanley Crouch says that

Filles is "Miles' last great jazz album." This is because Crouch is completely wrong about anything that happens after 1968. If you should ever watch Ken Burns'

Jazz miniseries, this will explain their omission or demotion of pretty much everything after hard bop. The

Complete Columbia box is redundant with the albums of the second quintet, but features a few more outtakes, as well.

In A Silent Way (1969) and

The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions (1969), and

The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions (recorded 1969). With both cool jazz and two of the greatest quintets in hard bop under his belt, Miles begat jazz melded with psychedelic rock and post-Stockhausen compositional music. Critics of time did not know what to make of it. They call it fusion, but much of the music they called fusion thereafter lacked Miles' sensibility and restraint.

In A Silent Way is an ouroboros, much like

Finnegans Wake, with each of the two tracks winding back around to the same piece of music that opens them, and each seamlessly flowing into the other. It is a perfect album, and often I will say that it is my favorite album, even though there are about a dozen albums that could claim that dubious distinction. The music is both driven and introspective. Unlike almost all jazz that preceded it, it is wholly a studio invention, with producer Teo Macero editing together the tracks from different recordings. It is the shape of music to come, and its influence can be felt throughout the sphere of interesting music regardless of genre. Lineup is Miles, Wayne Shorter (sax), Tony Williams (drums), Dave Holland (upright bass), Herbie Hancock (electric piano), Chick Corea (electric piano), Joe Zawinul (organ), and John McLaughlin (guitar). The

Complete In A Silent Way Sessions includes a few tracks from

Filles de Kilimanjaro, a few tracks that would drop on later compilations, and the rough tracks that became

In A Silent Way.

Bitches Brew, recorded a few months later and released in April 1970, has an even greater cast of musicians and employs even more editing by Macero. I do not have a copy of that album, but I do have a copy of the

Complete Bitches Brew Sessions, which includes all of the tracks from

Bitches Brew along with alternate takes, outtakes (many of which showed up on

Big Fun, released in 1974), and rough tracks edited down for the album. While considered a landmark recording, to my ears it is the inferior of both the studio album that preceded it and the one that follows, which is perhaps due to the mutable lineup including a number of musicians new to Miles' crew.

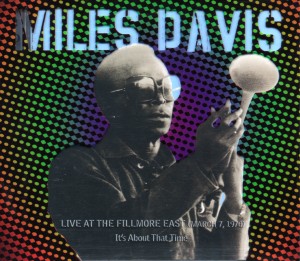

Juan-les-Pins, France July 1969,

The Lost Quintet Bootlegs, Discs 7-12 (all recorded November 1969), and

Live At The Fillmore, March 7, 1970: It's About That Time. Miles could not take his cast of thousands (ok, it's really about 20 or so) who played on

Bitches Brew out on the road with him, so he compiled a new quintet, often called the Lost Quintet because they never recorded an album together in the studio. At least they didn't record as a five-piece, since I believe all of them play on

Bitches Brew. The group is Miles, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, and Jack DeJohnette replacing Tony Williams on drums.

It's About That Time is an official release but the rest of these albums are bootlegs. And oh, sweet voodoo, are they all great.

It's About That Time is a recording of Wayne Shorter's last show with the lost quintet. Some of these also feature Airto Moriera on cuica and hand percussion.

A Tribute To Jack Johnson (recorded 1970, released 1971) and The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions (recorded 1970). My other favorite Miles album is A Tribute To Jack Johnson, which is the most heavily spliced album in Miles' catalog, pulling together chunks of music from many different sessions and ideas, along with a small portion of "Shhh/Peaceful" from In A Silent Way. Where Silent Way is introspective, Jack Johnson is aggressively funky and psychedelic. The interplay between John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock's guitars on the section called "Willie Nelson" is the closest to atonal noise that Miles ever reached, and its ugly beauty can rip your heart out. Unlike some of the other Complete box sets, The Complete Jack Johnson box is disc after disc of rough tracks. Some of the outtakes crop up on Big Fun and Live-Evil, true. But of any of the Miles box sets, this is the one that peels back the mask and delves into the wildly creative process with abandon. Awesome, in the sense that dumbstruck awe is my primary response to this music.

Black Beauty: Miles Davis At Fillmore West (April 10, 1970),

Miles Davis At Fillmore: Live At The Fillmore East (June 17-20, 1970),

Isle Of Wight (August 29, 1970),

The Cellar Door Sessions (December 16-19, 1970),

Live-Evil (recorded 1970, rel. 1971),

Live In Belgrade, November 3, 1971, and

Live in Cologne, November 12, 1971. These albums show how Miles was focused on his live sound over this year-and-a-half despite some churn in his band. After Wayne Shorter left, Steve Grossman stepped in on sax, and can be heard on

Black Beauty and

Miles Davis At Fillmore. Gary Bartz took over on sax and Keith Jarrett joined as a second keyboardist by the time of

Isle of Wight (a bootleg with one live track from the 1970 Isle Of Wight festival [one can hear this in its entirety on the new

Bitches Brew Live album] plus outtakes from the

Bitches Brew Sessions and the

Jack Johnson Sessions and, strangely enough the later

On The Corner sessions). Bartz and Jarrett were still in the band for the stellar

Cellar Door Sessions, some of which popped up on

Live-Evil, which was chronologically Miles's next release after

Jack Johnson. Chick Corea was out of the band by this time, and Michael Henderson had replaced Dave Carter on bass. Awesomely, John McLaughlin joined the band for one of the sets, which was, I think, the only time McLaughlin played with Davis live.

Live-Evil also features more

Bitches Brew and

Jack Johnson outtakes. By the time of the tour that the Belgrade and Cologne bootlegs were taken from, Jack DeJohnette was replaced on drums by Ndugu Leon Chancler with Charles Don Alias and James Mtume Forman replacing Moriera on percussion. The

Cellar Door Sessions is the best of these, but any and all of these albums are stunners.

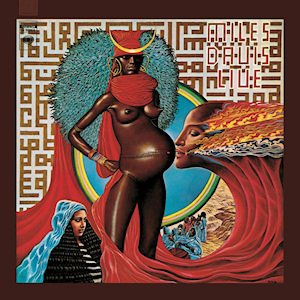

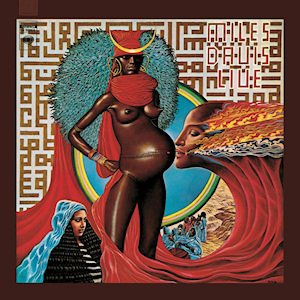

On The Corner (1972),

The Complete On The Corner Sessions (1972-1974),

Right Off: Complete Live At Paul's Mall, September 14, 1972,

Live At On The Corner September 24, 1972,

In Concert: Live At Philharmonic Hall (September 29, 1972). It is hard to express how incredible

On The Corner is. Bringing together the groundbreaking editing work from the previous five albums with a sense of psychedelic groove taken from funk, the propulsion of krautrock, and a repetitive structure taken from Stockhausen and minimalism,

On The Corner synthesizes all of these into a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, which is the essence of Miles' genius. There are 20 musicians credited for

On The Corner, including two electric sitarists and four percussionists. The

Complete On The Corner Sessions box includes rough tracks for

On The Corner, tracks that would later turn up on

Big Fun and

Get Up With It, and previously unreleased outtakes. It's almost as good as the

Complete Jack Johnson box.

Right Off and

Live At On The Corner are bootlegs recorded shortly before the official release

In Concert. All are excellent.

Big Fun (recorded 1969-1972, released 1974) and

Get Up With It (recorded 1970 - 1974, rel. 1974). These are two compilations released in 1974.

Big Fun reaches back to the

Bitches Brew Sessions and has outtakes from

Jack Johnson and

On the Corner, as well.

Get Up With It has four tracks recorded after

On The Corner (with the great Pete Cosey on guitar) and four from prior sessions back to

Jack Johnson. Both albums are phenomenal, and surprisingly coherent given their disparate recording times over a rather tumultuous period for Miles. But

Get Up With It has "He Loved Him Madly," a 30-minute tribute to Duke Ellington that is basically proto-ambient music (and Brian Eno has discussed how influential it was on his own ambient music). "He Loved Him Madly" is astonishing, even in the context of Miles' consistently astonishing output of the time.

Black Satin: Tokyo June 19, 1973,

Olympia July 11, 1973, Dark Magus (March 30, 1974),

Another Unity: Tokyo January 22, 1975,

Agharta (first set, February 1, 1975),

Pangaea (second set, February 1, 1975), and

Unknown Sessions bootleg (1972-1976). Four bootlegs and three live releases from the period in which Miles had the twin lead guitars of Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas in his band. This is the heaviest funk-space-jazz-krautrock-head music ever made, and considering its relative inaccessibility, it is the great lacuna of Miles's career. The

Unknown Sessions include some of the amazing recordings Miles made in the mid-70s with Cosey and Lucas. Some tracks from this period cropped up on the

Complete On The Corner box, but most are still unreleased.

Music From Siesta (1987). Unfortunately, Miles released only live albums and compilations between 1972's utterly brilliant

On The Corner and 1981's tepid

The Man With The Horn. I'm not a fan of Miles in the 80s, where he seemed more lost than anything.

Music From Siesta is not bad, though, with its deliberate references to Miles's Gil Evans period. Considering how many brilliant, game-changing, genre-shaking albums were in Miles's past, however, "not bad" is a damning assessment.