Book No. 45: The Turn of the Screw and Other Stories by Henry James

The "other stories" mentioned in the title were "Sir Edmund Orme," "Owen Wingrave," and "The Friends Of The Friends," all of which deal with hauntings of some sorts. The real prize here is, of course, "The Turn Of The Screw," a short story more perfect than I remembered from my freshman Victorian Lit class. James's prose is so carefully considered and honed that it renders the delicious ambiguities of the story to be completely hidden unless one is looking for the craft. His narrator is wonderfully unreliable, with most of her reported conversations ripe with potential meanings. We know what she is thinking, generally, but she passes so quickly over the specifics of how she learns certain things that a careful reader, when going back to re-read, will find all sorts of information she has glossed over in her haste to reach her point. I thought I didn't care much for James, but I think now (15 years later) that I'm going to have to re-read some of his novels.

Friday, December 30, 2005

Book No. 44: Master and Commander by Patrick O'Brian

Another fantastic read. I loved the movie, which is only marginally related to this book, and considering how highly recommended O'Brian's work is, I couldn't wait to dig into this. I often had no idea what was going on in the action sequences (which, hey, was true of the movie, too), but that wasn't so important. What was important was the life O'Brian breathes into the lost way of life of the sailing brig. I'm not going to write too much about this, because it's been done and done better, but I did enjoy the hell out of this book and intend to continue reading O'Brian.

Book No. 43: Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami

I've become quite the Murakami fan this year. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and Kafka On The Shore were both brilliant, so I was quite looking forward to this novel. Unlike either of the other two novels, which combine dream-logic and Pynchon-like playfulness, this one is more or less a straight coming-of-age novel set in the late 60s. However, it retains Murakami's masterful ability to make both the strange and the ordinary seem equally alien and perfectly familiar through his tap into subconscious portents. When reading his books, I feel like I'm only inches away from reading a very compelling fairytale.

At the start of the story, the protagonist of Norwegian Wood is reminded of his youth by hearing the titular song on an airplane, and the rest of the novel takes place in his past. His best friend has committed suicide a year before, and he has become friendly and perhaps fallen in love with his best friend's girlfriend. After sleeping with him, she puts herself into a rural mental hospital, which he visits periodically. He meets another girl in Tokyo in the meantime, with whom he also falls in love. All of this is wrapped in the glow of youthful self-doubt and white-hot feelings, and all of the characters are perfectly realized. I wouldn't start reading Murakami here, but a nascent fan like me would probably find this swerve into strict realism to be poignant and fulfilling.

Book No. 42: In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Kim Cooper

What a beautiful dream

That could flash on the screen

In a blink of an eye and be gone from me

Soft and sweet

Let me hold it close and keep it here with me

If you're like me, you love Neutral Milk Hotel's In The Aeroplane Over The Sea with a passion that few other albums achieve, and you have been looking forward to the 33 1/3 book for as long as you've known about it. Well, ok, there's probably only 1000 or so people in the country who fall into that category, but MAN, what a great album and what a great book about it.

Kim Cooper (the editrix of Lost In The Grooves, Bubblegum Music Is The Naked Truth, and Scram Magazine) gets to the heart of the story about this album. As NMH fans know, Jeff Mangum produced only one prior NMH album, On Avery Island (released in 1996), which was pretty much created without a band, then brought in a group that became the NMH that we all knew and loved. NMH put out the amazing In The Aeroplane Over The Sea in 1998, went on a short tour to support the album, then more or less disappeared. I remember when they came to Chapel Hill on that tour, but I didn't go see them because I thought I'd have plenty of options to see them again. I was wrong.

Cooper spent some time with Jeff Mangum while researching the book, and it shows, despite his unwillingness to be directly quoted, in her insight into his elusive genius. She also spoke with the other major members and friends of the band, who provided her with the in-stories that show exactly how this band bottled the lightning in 1998. Cooper's depth of research and sympathy for her subject are wonderful to read.

I pitched Richard and Linda Thompson's Shoot Out The Lights to 33 1/3, and I can say with confidence that this is exactly the sort of book I'd attempt to write about that album if the editors give me the go-ahead. Some of the other 33 1/3 books have been too much about the ego of the author; Cooper disappears into her narrative, and her book is infinitely better for it.

Friday, December 09, 2005

I set up a tentative website for the new band at Myspace. There's an old demo there and more to come.

Monday, December 05, 2005

Book No. 41: The Final Solution by Michael Chabon

Another Sherlock Holmes rewrite, Chabon's book is a bit more to my liking than Mitch Cullin's. As in Cullin's book, The Final Solution takes place when Holmes in very old, but this Holmes isn't reflecting on his life; he's engaged in a mystery. The mystery in this case centers around a parrot that spouts numbers in German, the only friend to a young mute Jewish boy who has been rescued to England during WWII. When a lodger in the boy's house turns up dead and the bird vanished, Holmes comes out of retirement to find the bird. The story briefly spends time with a colorful cast of characters (and the story is so short, a novella really, that everything is both brief and perfectly considered) before finally getting around to revealing the actual perpetrator through the perspective of the bird. Little is made of the fact that numbers that the bird spouts are almost definitely either the numbers of the trains carrying Jews to death camps or the numbers tattooed onto murdered Jews. Oh, and Holmes is never identified as such, being simply called "the old man" throughout the book, but his identity is barely a mystery. All in all, an interesting novella. I suspect that it contains metaphorical depths that re-reading would reward, but maybe not.

-----

A fellow in comments to Cullin's book invites viewers to visit his website, in which he inserts himself into the lead role in Doyle's Holmes stories.

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Anonymous asks in comments how Robert Clark Young is being disingenuous in his statements on Brad Vice's alleged plagiarism on this web page. Anonymous follows up by pointing out Young's article in the the current NY Press.

To the question of Young's disingenuousness, let me point out that Young compares Vice's use of some of Carmer's words to the institution of slavery and says:

The law states that the cut-off date is 1923. Writers are free to steal the phraseology--even entire texts--of any work published before that date. This is a federal law. True, white Southerners have a long history of ignoring and violating federal law, making up excuses for why it should be "nullified," ranging from the South Carolina Nullification Act to secession to Jim Crow laws to Wallace standing in the schoolhouse door to the illegal placement of the Ten Commandments on state property to Jake Adam York's justification for stealing KKK stories from the dead.You want to know why I call this guy a nutcase? Please read and re-read the above, which explicitly compares white Southern writers, a list that presumably includes Faulkner, O'Connor, Harry Crews, Larry Brown, Eudora Welty, Madison Smartt Bell, Bob Shacochis, as well as the Barry Hannah he wrongly hatchets in his NY Press article, to pathological racists from the past. The condescension he exhibits in this argument states almost everything I need to know about the guy: he's an unredeemable prick.

What we need is a literary William Tecumseh Sherman to ride down there with a few thousand good men and make sure you boys play clean. No wonder those folks in Georgia were so quick to rescind Vice's Flannery O'Connor award--they were quick to attempt to squelch this embarrassment before the story hit the Northern press and Yankees felt the righteous need to "come on down heah and interfere"--the traditional fear of white Southerners.

It's too late of course. This story will not limit itself to the Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia papers that have run it. The Chronicle of Higher Education, a Yankee paper, has run the story, and other Yankee papers will follow. I ought to know. I write for Yankee papers and have already contacted The Editors. Vice's volley against the Fort Sumter of Literary Ethics must not go unanswered.

Then, in his NY Press article, he reiterates the current charges against Vice (calling for his hanging? what?), claims to have found further evidence of plagiarism, and then bitches about the chumminess of writers associated with the Sewanee Writers' Conference.

Leaving aside the first issue because I've already stated my opinion on it, Young's alleged new evidence of plagiarism is pure bull. Young states that Vice could have rewritten those phrases in his own words, and, well, they are. What's more, this grand evidence is bland to the point that it could appear verbatim in almost any number of books about blowflies.

Finally, regarding the chumminess of the participants at the Sewanee Writers' Conference: well, I'm shocked, shocked, to learn that writers, especially literary writers, most of whom will have to have other jobs since their fiction will not ever pay the bills, may occasionally play the you-scratch-my-back, I-scratch-yours game. That's quite the scoop there. No doubt Mr. Young is above all of this because of his superior Yankee upbringing.

------------------

Update with links.

Fred of American Views Abroad offers a more succinct (but more clever) analysis of Mr. Young's article.

Jason Sanford at StorySouth weighs in with a more thorough analysis, including a rather convincing rebuke of Mr. Young's flimsy "new evidence" of plagiarism.

Michelle Richmond's shows the allegations of mutal back-scratching at Sewanee to be as fictive and twisted as the rest of Mr. Young's article.

After reading these other, better-conceived posts, it's obvious to me that Mr. Young is pursuing a personal vendetta against Brad Vice for unclear reasons. And here I thought Armond White was the worst writer at the NY Press!

Monday, November 28, 2005

Book No. 38: The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett

Book No. 39: Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett

Book No. 40: The Thin Man by Dashiell Hammett

I had a hankering to read some Hammett. Years ago, I went through several weeks of reading nothing but the man, including the novels I'll discuss today, but memory had erased many of the all-too-enjoyable particulars of his writing. Anyway, The Maltese Falcon is a ton of fun, even when it doesn't add up, and, given the way Sam Spade talks, almost impossible to visualize without Humphrey Bogart in the lead. One of the things time had left a bit murky for me was the story Spade tells of the man named Flitcraft, the subject of the overwhelmingly great Mekons song.

The spiritual basis for countless movies, including the truly wonderful Yojimbo (and, by extension, A Fistful of Dollars) and Miller's Crossing, Red Harvest is the Continental Op at his cynical best, destroying a criminal syndicate's hold on a mining town for the sheer amoral thrill of it. If I remember correctly, Red Harvest was Hammett's first novel, and it is interesting how differently Red Harvest is written than The Maltese Falcon or The Thin Man. All three share first-person narrators who don't share their thought process or realizations with the reader, but Red Harvest's Continental Op is a more blunt thinker than Sam Spade or Nick Charles (by a large margin there), as if Hammett were channelling the the less refined business of being an unwanted gun-for-hire. If Spade is the dispassionate and jaded heart of detective fiction (not to mention the archetype for Chandler's Philip Marlowe), the Continental Op is the tough-guy mold.

From Hammett's first novel to his last! The Thin Man (obviously influenced by or co-written with Lillian Hellman) is witty as hell, but in a different way than the movie, which is one of my favorites. Nora Charles isn't as much a participant in the case as she is in the movie, and the dramatic conclusion is quite different, albeit more satisfying as literature. Everything about this book is practically perfect, from the goofy pop-Freudian psychology to the oh-so-sophisticated drunken sexual shenanigans. Hammett was at the top of his game with this one.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

I'm unable to stop blogging today, so I want to mention my support for Brad Vice and outrage over UGA's pulping of his book.

Brad's an old friend to both my wife and me and has always been an extremely conscientious guy. By all appearances, his crime is taking language from a nonfiction book that he acknowledged verbally, although - fatally - not in print, and putting it into the perspective of his fictional characters. It's a screw-up, definitely. UGA's response has been to rescind Vice's Flannery O'Connor Award and (here's the part where damnation enters the picture) recalling and pulping the man's book as if it were a Firestone tire about to blow out!

See for yourself:

Tuscaloosa Knights by Brad Vice.

Flaming Cross by Carl Carmer.

Here's some discussion:

The Literary Lynching of Brad Vice

Fell In Alabama: Brad Vice's Tuscaloosa Night (and check out the nutcase named Robert Clark Young who comments as disingeniously as Karl Rove speaks)

I know Brad doesn't read this, but this thing happening to him is a goddamned shame, made worse by the hell of good intentions. That library reader who's so-obviously biddying herself about the press by repeatedly calling Brad a thief: shame on you, lady. Your desire to right the wrong of not mentioning Carmer's influence is admirable. Your moralizing about it is way over the line. And the head of the UA Press who more or less demanded that UGA pulp the book rather than include an acknowledgement: shame on you, too, you publicity hog. Way to support a hometown writer.

Brad probably deserves a "shame on you," too, but I'm sure he's beat himself up over this worse than anybody else could. Mississippi State is even reviewing his job, which goes to prove that there's nothing people love more than to fan flames at the trainwreck.

Slate has various people talking about their favorite books from college. One of my two "hell yeah" moments was for college dropout Judd Apatow's list.

Book No. 37: The Wild Palms by William Faulkner

As some readers of this blog may remember (Ha! "Readers of this blog." I amuse myself.), I was thinking about this book after the flooding of New Orleans. It's essentially two interwound novellas, one ("The Wild Palms") about a tempestuous love affair and the other ("Old Man") about an unwillingly escaped convict on the loose during the Flood of 1927. I read "Old Man" by itself just a few years back, but I hadn't read "The Wild Palms" since I was in my early 20s. Well, that was probably for the best.

"The Wild Palms" contains some beautiful - no, perfect - Faulknerian sentences and imagery, but those of us outside of our idealistic romantic period will want to smack the lovers at the heart of the tale upside the head. The transformation of the male side of these star-crossed idiots from a taciturn naif into a jaded logonorrheac poet is as unconvincing as their collective willingness to destroy each other attempting to keep their illusion of love alive. Bah, humbug.

On the other hand, "Old Man" is major Faulkner, as great as Absolam! Absolam! and Light in August. In the story, a naive, idealistic young convict (who is similar to the young man at the heart of "The Wild Palms" in some ways) is swept away by the water while rescuing a pregnant young woman during the 1927 Mississippi River flood. The plot unfolds with picaresqueish deliberation, as the convict encounters misadventures, is shot at again and again (in some encounters reminiscent of Huckleberry Finn), assists in the birth of the child while escaping snakes and a mudslide, defends the skiff, hunts alligators barehanded, is caught and released by a sympathetic Louisiana doctor, and ultimately winds up with an extended sentence. It's the funniest Faulkner story I've ever read, and still full of poignance and a sense of outrage over the treatment of inmates and the lot of the poor. I wish Oprah had recommended this story to the general public to be their first exposure to Faulkner rather than her more complicated choices.

Although the chapters are intermixed in the book, neither has much in common, other than the cluelessness of the leading men. "The Wild Palms" plays that cluelessness for tragedy and "Old Man" for comedy (with a more subtle tragic theme). Both reveal the end of the story fairly early on. Both contain passages so lovely and profound that the reader has to stop and catch his or her breath. But that's true of most of Faulkner's work.

Finally, an excellent article on Ronnie Earle, Travis County's beleagured DA, in the national press. In Salon, but well worth clicking through the ads. Let it be known that, as far as I'm concerned, Earle's doing the Lord's work in taking down Tom DeLay and his thuggish approach to political dissent. Give him hell, Ronnie!

Monday, October 31, 2005

Book #36: A Slight Trick of the Mind by Mitch Cullin

I read a few of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes short stories a few months back for the first time since I was a child and found myself enjoying them as much for the view into the Victorian mindset about crime and police as the my somewhat nostalgic feelings about the actual stories. Mitch Cullin's A Slight Trick of the Mind is an attempt to fix Holmes in time and add a dose of emotional humanity to the character by setting it after WWII with a Holmes who is 93 and suffering from natural memory loss. This Holmes isn't trying to solve a case, and the only detective work we see is in a fifty-year-old case Holmes is writing about, one where he becomes enamored of a young woman who is forever beyond his reach. Instead, he spends time with his housekeeper's son, who is managing his apiary, and thinks about a recent trip to Japan.

It's not a bad novel, but neither is it a great one. Holmes hardly seems like Holmes, which Cullin explains by having him constantly describe the famous stories as fictions by John Watson, but it seems cheap to appropriate a major character of fiction only to modify that character under the guise of adding new dimensions. I don't know. I can't imagine this story being interesting (and it was interesting) if there were another elderly man at its heart - if, for instance, Cullin had written the exact same story but changed the name of the central character - but the story as it is is unsatisfactory, not because Holmes is sacred, but because he is a collection of behaviors, a characterization, not a real person. Maybe that's the point. There's a certain wit to having Holmes tell others that he never wore a deerstalker hat or smoked a pipe, but there's also a certain shorthand involved in asking readers to feel a certain way about the central character because of our pre-existing knowledge of his fictive life.

Anyway, I liked a great deal of the story, but disliked the blatant manipulation on display towards the end of the novel. If you've read it, I think you'll know exactly what I mean. I'm planning to read Michael Chabon's Holmes retread in the near future, too, so I'll have something to compare with this.

-----------------

On another note, this is my 36th book of the year. With a mere 9 weeks left in 2005, I don't think I'm going to read another 14 books. However, I intend to continue reading and reporting on them and will perhaps continue this challenge into the new year.

Oh, I didn't finish George Pyle's book Raise Less Corn, More Hell before the library needed it back (and thus didn't write about it here), but I enjoyed the half of it I read.

No other personal news to report at the present. I added the blog Critical Culture to the list at right after reading the author's interesting take on a few books and movies over the last few weeks. New parents like myself should read Emlyn Lewis's blog. I knew the guy a million years ago when we were young, and back then he was one of the most intelligent people I had ever encountered in my brief experience. It's many years later and I've met a lot more people, but Emlyn is still about the smartest and most incisive person I know. I'm happy he's turning his smarts on being a dad, because it saves me a lot of soul-searching. Oh, and I'm adding a link to Ludic Log Leonard's LiveJournal Skullbucket, because that's where he's putting his best stuff these days. Go today to read his Halloween awesomeness, especially the best H.P. Lovecraft tribute/ripoff I've witnessed.

Monday, October 24, 2005

Book #35: Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Not long ago, I wrote a song about clever novelists comparing the best of them with magicians pulling out the rug from beneath the reader, who can only sit there, open-mouthed, visibly shaken but physically unchanged. It's not a very clever song, I know, but Ishiguro is such a magician. I read this novel in such a rush that I had no idea how affected I was by these characters until, suddenly, with just a few words near the end, Ishiguro ripped my still-beating heart out before my stunned eyes. I mean, here's the trick: Ishiguro told me all along what was going to happen and who was going to suffer from it, and when it inevitably happened, I was more shocked than if it were completely out of the blue. And I was even more surprised by how much it affected me. When did I start to care? How did I go from being a moderately engaged, somewhat cool reader to being a tear-soaked, weak-kneed mess in just a few words?

Poof. Voila!

So, the novel. As I assume you know, it's written from the point of view of a young woman, Kathy H (there is no more to her last name, but the evocation of Kafka with his single initials is deliberate) who happens to be a clone. Her worldview has been deliberately limited throughout her entire life and Ishiguro imagines the four corners of this particular education with unbroken clarity. She is entirely believable as the product of the upbringing she describes. Much of the book is taken up with her memories of Hailsham, the institution that raised her and her small circle of friends. As in the horrible A Separate Peace, the novel captures the boarding-school cliches, but Never Let Me Go makes them its own, mainly because of the peculiarity of the residents. The two people most important to Kathy are Tommy, a star athlete who is mocked because of his poor art skills, and Ruth, a manipulative, somewhat mean, girl who is Kathy's closest friend. Kathy doesn't exposit about her situation, but it soon becomes clear what she is and what her life has been like. It would ruin the narrative spell to give too much away, but attentive readers (and we're all attentive readers these days) will notice quickly that Kathy's is a smart-but-normal woman with a somewhat emotionally stunted girlishness in a horrible, horrible circumstance, one with a horror to it that is barely articulated in the novel. But the horror is there, creeping around the edges, seeping into the narrative cracks like a fog. By the end, it's so strong that you'll be astounded, suggestable, a ripe mark for literary sleight-of-hand. Fortunately for you, Ishiguro isn't interested in picking your pocket, but in subtly implanting the seeds to larger ethical issues. No cheap stunt magician, this is the work of a master wizard.

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Great Jonathan Lethem interview, responding obliquely to that godawful skewering from John Leonard I posted about lo those many months back.

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

Haven't finished a book in over a week, but I will soon. In the meantime, this'll put a little marzipan in your pie plate, bingo:

Thursday, October 13, 2005

I should mention that I went to see the Gang of Four last night, which was well and truly mindblowingly, ass-shakingly, skronk-skronkingly great.

The songs performed, in no particular order: Return the Gift, Not Great Men, Natural's Not In It, At Home He's A Tourist, Anthrax, He'd Send In The Army (according to Pitchfork, it was probably a microwave Jon King was whacking with a baseball bat just outside of the view from our vantage point), Paralyzed (I could be wrong about this one - should've taken notes), 5.45, To Hell With Poverty, Outside the Trains Don't Run On Time, Ether, Damaged Goods (encore). MIA: "I Found That Essence Rare" and "Contract," but I'm not complaining.

In this Salon article, some blowhard named Steve Almond discusses a blogger who hates him and name-checks High Hat contributer Robert Birnbaum.

From the article:

------------------------------

Here is a direct transcription:

1:41 - Steve Almond is standing right in front of me ... We haven't spoken; he's talking to Jim ... Wondering if he'll punch me out ... I think I could take him ...

As sad as this might seem, even sadder was the response of his fellow blog bitches. One of them, a guy named Robert Birnbaum, sent the following response:

Yo! Fo! Shizzle! Almond b a wus. He gotz to be got.

Remarkably, Birnbaum is not a young, African-American blogger from Compton who goes by the street handle OGB (Original Gangsta Blogga). He is a paunchy middle-aged Jew who conducts long interviews with writers for his lit blog, often mentioning himself and his dog Rosie. Having been interviewed by Birnbaum myself, I tend to think of him as the Regis Philbin of the lit game, though that may be overstating his charm.For the record, Birnbaum: If I get wind of you dissing my junk ever again, I'm gonna track down your mutt and see how she like my chocolate bone.

Why?

Cuz that b how real authors do they bidness.

----------------

The funniest part about all this is how right the Almond-haters are. I'd never heard of him before reading this, but is there a wussier action than threatening a man's dog in an article in a national magazine?

Edit - Actually, I found a few things interesting in the Almond article, including his attempts to engage his nemesis. Therefore I retract the term "blowhard" and substitute the more neutral "somewhat whiny guy" until future notice.

Monday, October 10, 2005

Book #34: The Preservationist by David Maine

The Preservationist is an odd novel: a rather modern-naturalistic retelling of the story of Noah (known here as Noe), complete with odd miracles (or incredible coincidences, sure), as told by Noah and his family. The story of the ark and the flood has an unreal fairy-tale quality that I've glossed over in my own head due to its pure familiarity (not that I'm saying that I believe in the story - I'm saying that I've never really thought about how odd it is, just how impossible).

Maine's stories vary in and out of first-person (strangely enough, it seems in my memory that only the parts of the tale from Noe's perspective are told third-person), handling Yahweh's occasional conversations with Noe and a few experience unlikely enough to be miracles with a deadpan nonchalance. Maine lingers over the details of Noe's attempt to build the ark (fortunately, his second son Cham - or Ham in most English-language Bibles - has learned shipbuilding skills) and to collect the animals (he sends his daughters-in-law North and South after animals with no money or provisions) and the somewhat hellish experience of travelling in a floating zoo. Characters ask themselves why they are building the ark, why Yahweh has chosen to flood the world, and, most importantly, why they survive when others die.

Maine also captures the primitiveness of the time. Noe and his family hardly have sophisticated ideas about sex, which happens all the time, and are aware, though just barely, of their similarity to animals in that regard. The ark is full of shit, which must be carried up to the rail and thrown overboard constantly, although the deck is also covered in shit - bird shit, almost an inch thick. Noe, who is 600 years old (in a world only 1000 years old, at least as far as the characters are concerned), tells stories about the disappearance of the hunter-gatherers. Noe rejoices in the drowning people (although others in his family are traumatized by the children he refuses to help) around the ark as the world turns into a giant ocean. When Noe gives an order, his children don't even hesitate before obeying.

All in all, a brilliant novel. It most reminded me of Jim Crace's Quarantine, which put a humanist face on Jesus's ordeal in the desert, a story in which, like in the Noah story, few of the nitty-gritty details appear. Unlike Maine's novel, in Crace's book God does not appear, nor are there any unlikely circumstances/miracles. However, both allow for the ambiguous possibility of the Old World God acting directly on the world as much as the possibility that people read miracles into coincidence. Admittedly, the events in Maine's book are far less likely to be anything but actions of an angry god, but Crace's book (and I should point out that Crace is an avowed atheist) ends with an image of a possibly Already-Risen Jesus following some of the other characters across the desert back to civilization. Maine also provides a certain sense of why people reject the capricious Yahweh, why Yahweh forms his covenant with Noe (not to destroy the earth again, as symbolized by the rainbow, just so), and lays the groundwork for how evolutionary thinking will eventually change the way that people understand history.

Maine has a second book out, about Adam and Eve. I intend to read that one, too, with due diligence.

Friday, October 07, 2005

Book #33: Incompleteness: The Proof and Paradox of Kurt Gödel by Rebecca Goldstein

Gödel was the most brilliant mathematician of the 20th century, and Goldstein, a novelist and philosophy professor (according to one of her anecdotes, she's roughly a contemporary of Rorty's), finds a way to explain his incompleteness theorems in plain language, wrapped up inextricably with the story of Gödel's life. Gödel was a lonely man, at odds with almost everyone he met other than Einstein, and Goldstein provides a narrative that demonstrates clearly why Gödel felt like an exile all of his life, even in the occasionally loving arms of Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study.

It's in her description of his philosophy that Goldstein really shines. She places Gödel's incompleteness theorem, which I've seen used to both support and refute positivism (that's the notion that there's no objective reality unmeasured by humans), in its proper context, which is to refute positivism and uphold Gödel's Platonism. She also carefully shows why Gödel and Wittgenstein (arguably the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, and certainly in a class with few others) disliked each other and refused to engage each other's philosophies, despite the fact that she believes that the Tractatus-era Wittgenstein (that's the early Wittgenstein of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, mind you, before he became interested in deconstructing language) and Gödel were more-or-less in agreement.

Heady stuff, and it's admirable that Goldstein made into such a light read. I'm certainly not a Platonist - in fact, I feel quite a bit of kinship for Rorty's anti-essentialism, which leans towards the positivists - but I also believe that it's a hubristic mistake to discount the ineffable (much like the Tractatus, which ends "Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we must remain silent."). Despite my own prejudices against Platonism, I found myself able to appreciate Gödel's elegant theorems as both mathematical and philosophical positions, and found a greater understanding of the logical-mathematical side of philosophy, which has always previously left me cold (and is one of the main reasons I've had trouble understanding Wittgenstein and Quine, despite my admiration for both). Anyway, Incompleteness is a great book for lovers of philosophy or math from the general public, but not the practitioners. Then again, it ain't for them; it's for the rest of us.

Monday, October 03, 2005

Book #32: Kafka On The Shore by Haruki Marukami

As diligent readers of this blog (Ha! See what I did there?) will note, I read and thoroughly enjoyed Murakami's The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle earlier this year. Perhaps due to the apparently more complete translation, Kafka on the Shore has a more holistic feel to it, although it never achieves the great high points of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.

The narrative follows two main characters. Kafka Tamura is a 15-year-old boy who runs away from his distant father and the Oedipal prophecy/curse his father placed on him when he was young. He finds refuge in a small town private library run by a friendly young man and an attractive middle-aged woman who may or may not be his long-absent mother. Meanwhile, Satoru Nakara, a simple-minded elderly man who can speak with cats, becomes involved with a supernatural plot that leads to an unwilling murder, rains of fish and leeches, and a search for a mysterious "entrance stone" that opens an inexplicable door. Their stories are intertwined in ways not immediately apparent.

This is obviously the stuff of fairy tales and the subconscious mind, and Murakami gives it a full rounded life of its own. I thought several times of Neil Gaiman's American Gods, which wanted so badly to mine this territory but fell painfully short. The pop culture references and perfectly captured character study reminded me of Jonathan Lethem's work and, as with The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, I could picture the action - well, some of it, at least - only in the shimmering anime style of Miyazaki (which, of course, may say more of my slim knowledge of Japanese culture than anything). All of these analogies point to two things: 1) Murakami falls into the comic-book-meets-intelligentsia style of Gaiman, Lethem, and Miyazaki, and 2) I am a big ol' geek.

To be fair, Murakami also suggests other, more high-falutin' Western writers, such as Garcia Marquez and Borges (although not so much Kafka, so... ok), and I understand that much of the book is a tribute to one of the authors Kafka reads during his lazy days at the library in the beginning of the book.

Well, this isn't kid stuff, anyway. Murakami is interested in dreams and the origins of the subconscious, which in this case means that the book has several graphic sex scenes, all between ambiguously inoppropriate partners, graphic violence, and various ways in which the nasty things from Grimm's fairy tales (or Jung's archetypes) slither into a naturalistic setting with deft ease. Yeah, that's the good stuff.

Book #31: Thelonious Monk: His Life and Music by Thomas Fitterling

Fitterling's book is translated from the German, and the first section, which details Monk's life, definitely reads like a poor translation. I didn't know much prior to reading this book about Monk the Man, though, and even in bad translation, Monk's story has interesting points. The second section, which consists of a detailed analysis of Monk's style and each of his recordings, is indispensable reading for Monk fans. Steve Lacy's introduction is also fascinating, simply by virtue of being a firsthand account of working with Monk the Man by one of the great interpreters of Monk the Musician.

Thursday, September 29, 2005

Wednesday, September 28, 2005

Monday, September 26, 2005

Tokai '62 Strat replica

6

6

Catalinbread Chili Picoso Clean Boost (with fringe)

6

Loooper 2 Loop with Tuner Mute

5back to Loooper

5back to Loooper Loop B 6

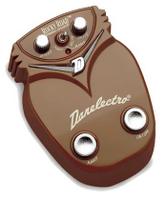

Danelectro Rocky Road Rotating Speaker Effect

5back to Loooper

6

Morley A/B/Y Router

Loop A 6

1965 Fender Princeton Reverb

Loop B 6

Boomerang Phrase Sampler

6

mid-70s Sunn Alpha 112R

Book No. 30: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Like many of us, I read this when I was a kid shortly after reading Tom Sawyer for my 6th or 7th grade English class. I imagine that my school didn't consider the repeated use of the word "nigger" to be much of an issue, seeing as how I grew up in Alabama in pre-politically correct times (I believe that finally reached Alabama last March).

Anyway, much of the significance of this novel was lost on me at the time. I recognized that Huck changed, and changed a lot, over the course of the story, but I didn't have the history or maturity to recognize quite how drastic his change was or quite how cutting Twain's sarcasm was in his day and age. I'd seen Huck's decision to rescue Jim mentioned occasionally as a phenomenal point in American literature, but I'd forgotten that Huck thought that helping an escaped slave meant that he was damned. I'd forgotten - or never realized in the first place - how monstrous Tom Sawyer is at the end of the book, with his frivolous, idiotic insistence on making Jim's escape into a game and his fundamental lack of respect for Jim's humanity to never even mention that Jim's been already freed so that Jim and Huck will play his game. Tom Sawyer is a child, yes, mostly unaware of the consequences of his actions, and it's fairly clear that in allowing Sawyer to do evil as part of his game, Twain is indicting a culture that values life so poorly as to create a game of slavery.

The points leading up to Jim's bondage and freedom are, of course, magnificent. The novel is about games and deceit, from the idyllic Jackson Island interlude, where Huck and Jim first form their friendship, to the danger of the fog on the river, where Huck learns in perfectly terse prose what it is to have a conscience, to the bloody feud, which further builds on Huck's knowledge of consequences, to the Dauphin and the Duke, where Huck learns how quickly deceivers will betray their comrades. Hemingway, who championed this book as the best of American literature, supposedly hated the final section, and I certainly found it frustrating. However, I think it was necessary for Twain to demonize Sawyer to make his narrative complete.

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

I stole this link from the inimitably wonderful Maud Newton. I hope it brings as much pleasure to y'all as it did to me.

Excerpt:

For starters, I have watched your goings-on for some time now. The fin de siecle appearance of your administration, especially after the rampant degeneracy of that satyr Clinton and his panting ilk, was a most welcome disruption of the general malaise of things. You effected revolutionary and deleterious change on the rosy status quo. How I hated that corrupt, fallen status quo. (Incidentally, this falls rather in line with a scheme I posited—which you no doubt have noticed in your readings—wherein pederasts and degenerates would be encouraged to gain high office—the presidency, perhaps—which station they would then neglect as they attended to their sexual and narcotic appetites. There would be no more war, because there would be no one to start the wars—everyone flitting off to parties and such. Your scheme, however, one of sustained, systemic breakdown, appears to be the work of quiet genius, even if it has had the regretful, short-term effect of increasing the

incidence of war.)You stemmed this people’s lemming-like rush after prosperity, you marshaled lagging school children, and you brought zealous religiosity again to the national discourse. You rebuked the Old World! You felled Babylon the Great! (The lazy asses, the picayune media [those bankrupt souls], might raise captious and frivolous objections to these deeds, but, Sir, say to you [as even God himself might say]: WELL DONE.)

...

In the meantime, Mr. President, I offer you my jubilant, shining hand of friendship. Together, liveried in the costly apparel of high station, and much as Joseph of Egypt and his trusty servant boy, Tut-tut, long ago once did do, we shall step down from our aerie to bid Louisiana and parts of Mississippi gather at our feet. We shall tell them to rise up and thrive! Be industrious! And they shall do so, and be so.

So long, Big Pardner (a little Texan, in honor of your noble heritage)!

Yours most ardently,

Ignatius J. Reilly

Monday, September 19, 2005

Book #29: The Elementary Particles by Michel Houellebecq

Perhaps I am an idiot. I don't understand why Houellebecq is constantly compared to Camus in reviews of this book. Both men are French and interested in ethics, but that's where the comparisons end. Houellebecq is more similar to Celine in his repulsion towards society and overriding disgust with humanity, but his muse is Nietzsche, pure and simple.

The half-brothers of this book, Michel and Bruno, appear to represent Nietzsche's intellect and physicality, respectively. Michel is barely in the world, a mostly asexual scientist who will ultimately destroy mankind in favor of an immortal, psychologically-superior über-man. He is interested (vaguely) in the world, but his opinions (which he mostly keeps to himself) revolve around the causes of pain, sex, and death, to which he blames uncertainty in an overly liberal, overly permissive society. His primary model is Bruno, a former teacher with a raging sex addiction. Bruno longs to be an alpha male, bringing his will to power to bear on the world around him, but he is instead a sad sack, constantly hesitating at crucial moments or acting out his fantasies inappropriately. He achieves happiness during the novel when he meets another sex addict, Christaine, at an intentionally grotesque hippy-dippy retreat, and travels with her to a permissive sex retreat that would inspire de Sade.

Both brothers were abandoned by their criminally negligent mother, a self-obsessed proto-hippie, and were raised by their grandmothers on their fathers' side. Both tend to give speeches rather than communicate, a writing tic somewhat explained by the epilogue (perhaps they are intentionally bad, but perhaps they are just a problem with Houellebecq's writing - I reserve judgment), as are the somewhat funny asides throughout the prose (such as a digression on mating rituals in rats juxtaposed with Michel's crucial inability to kiss the young woman who loves him).

Despite the graphic descriptions of sex and late 20th century anomie, the novel has the sensibility of an earlier age. Each brother tells his history in the type of detail often found in Victorian novels and there's a distinct pre-modern feel in all of the interactions, as if realism never happened in fiction, which is carried through to the sudden sci-fi ending, more like the jarring early fantasy-based sci-fi of H.P. Lovecraft or H.G. Wells rather than the modernist-influenced, "realistic" sci-fi of the 20th century.

My understanding is that this novel was quite controversial in France when it was published 8 years ago, which sort of makes sense, given its unrelenting assault on the state of emotional lives in the modern world, but sort of doesn't, given that most of Houellebecq's points have been around for over a century, given his tendency to echo Nietzsche and Celine. Houellebecq is also apparently playing the literary bad-boy to the hilt in interviews, but I really could not care less about the guy himself. Hm, I think I'm out of comments about the book, so I'll leave it here.

The only review I've thus far read that a) doesn't resort to hyperbolic rhetoric and b) has a grasp of literary history. I'm deeply disappointed in the NY Times reviewers in particular, but also saddened that J. Hoberman's review in the Village Voice was so much weak tea.

This article from Salon talks about the reprehensible actions of my Senators, Kay Bailey Hutchinson and John Cornyn, who are trying to make second-class students of the Katrina refugees. Way to show your Christian charity, you two! Maybe y'all can joke about in the future when you're hanging out on Trent Lott's new porch.

Monday, September 12, 2005

Book No. 28: Portnoy's Complaint by Philip Roth

I had never read this before. Now I have.

I was originally going to elaborate, but I believe that I have passed my quotient of bitching for the week, so I'll just say that I would probably have found this book shocking, funny, and true as a teenager or perhaps if I had been born in the 30s and read this when it came out in the mid 1960s. However, I read it as an adult in the double-aughts, and found only a mild chuckle or two for Portnoy's histrionics. Oh well.

Thursday, September 08, 2005

Wanna feed your righteous anger? Here you go.

In other news, I'm sure that Nero didn't want to play the blame game about his musical proclivities during that little fire in Rome, either.

Tuesday, September 06, 2005

Books No. 26 and 27:

Where Dead Voices Gather by Nick Tosches

Arthur Lee: Alone Again Or by Barney Hoskins

First, lemme ask: does anyone else feel like re-reading The Wild Palms? For some obscure (ahem) reason, it's been on my mind since last Monday. Something about the dual grace and evil of man in the face of a natural disaster of tremendous import, a flood even, something about this topic seems altogether appropriate to how I feel this week. I need to find my copy post-haste.

Maybe it's just me.

OK, onward to the topic at hand.

These two books are polar opposites. Tosches's book is an examination of the life of Emmett Miller, the blackface minstrel who, as Tosches argues, was a fundamental influence on such country luminaries as Hank Williams, Bob Wills, Jerry Lee Lewis, as well as an examination of the history of blackface minstrelsy and how it informed the pop music that dominated the 20th century. My friend Dutcher advised me to avoid this book as being overly well-researched. This turns out to be an accurate summary of the book's strengths and weaknesses: it is jam-packed full of information, often tangential at best to the central argument, sometimes fascinating and sometimes just tiring. Central to the book is the twist of race at the heart of 20th century pop music: white men (Elvis et al.) mimicking black men (blues artists of the early 20th century) mimicking white men mimicking black men (blackface minstrels).

Hoskins's book, on the other hand, is about a black man (Arthur Lee) who made some of the most interesting "white music" (that is, late 60s psychedelic rock stew, which, historiocity be damned, is usually considered white music) ever recorded. Unfortunately, unlike Tosches's book, Hoskins has contented himself with cursory research, easy (and sometimes unanswered) questions, and no challenges to the conventional wisdom regarding the band Love or their masterpiece Forever Changes.

All of which is quite a shame, as Hoskins writes for Mojo Magazine, the magazine for thinking rock fans, which also endorses this book. One would expect from the cover that it would be brilliant and illuminating. Too bad. I did learn a few things, such as What Happened To Bryan MacLean (he became a bitter born-again surfer dude and hey, did you know that he was Maria McKee's half-brother?) and that Arthur Lee didn't fire the gun that got him thrown in jail. However, almost no mention is made of Lee's very obvious mental problems or the fate of the other members of Love, nor are deeper questions asked about how Lee's race played into his fall from grace.

Tosches did ask the uncomfortable questions, and sometimes he even labored to answer them (and did a fine job at that). It's too bad that he (and his editors) are so close to this subject that they couldn't figure out that there's several books' worth of material lying uneasily together within these chapters, making large sections of the book uneasily redundant or hopelessly divorced from the central point Tosches was trying to make. Maybe the topic itself is so large that Tosches literally could not get his head around it; there's no shame in that. Either way, Where Dead Voices Gather should have either been broken into at least three other books or enlarged to 800+ pages. A co-author may have helped sort the material. A decent editor could have also helped to organize and cut out redundancies (several times, Tosches repeated near-verbatim the same piece of information only several pages apart).

However, Where Dead Voices Gather is a major work of pop-culture scholarship. Arthur Lee: Alone Again Or is most decidedly not.

And The Wild Palms, which consists of two novellas, the second of which is about a nameless convict who rescues a pregnant woman from the flooding Mississippi River, is one of the greatest books of all time, packed with so much truth that it makes grown men weep.

Thursday, September 01, 2005

There's various articles I should link to about New Orleans, but I'm going economical here.

This is what hell is. You ever read Saramago's Blindness? He was right.

This is only one example of why my friend Leonard deserves a MacArthur Grant. I regularly wish I had half of his smarts.

Wednesday, August 31, 2005

I love New Orleans. I grew up near enough to make clandestine overnight visits often when I was a teenager, and almost all of my most outrageous drunks have taken place down there. I've been back many times since, and I've always had a phenomenal fun time there. I've never personally run afoul of the celebrated crime in the city, although everyone I know who has actually lived there was robbed more than once.

My heart goes out to the people who've lost everything to Mother Nature, and especially to the people still there, those too poor or stubborn to get out of the way of the greenest of tooth and claw, many of whom may not last the week.

However, I say we should abandon it. When Nature makes a point as unambiguously as She did with New Orleans, it is perhaps best to collectively take step back and allow ourselves to simply be awed by how small our works are in comparison. Too Schopenhauerian for you? Think of Pompeii. The Romans had the good sense to read the writing on the wall.

I'm not a religious person, but I think I could make a good argument that regardless of whether you attribute divine intelligence to it or not, raw Nature -- pure dynamic force -- is unanswerable and truly awesome, and it has taken New Orleans almost as an afterthought, partially spurred on (or at least omni-causally spurred on) by this nation's own destructive environmental policies. I only wish it could have taken Colorado Springs instead, because I fear that the self-righteous bastards are going to claim this as God's punishment of a wicked (and, incidentally, mostly black) city.

The Blackness of New Orleans is another point that is sticking deep in my craw. The media has spent an inordinate amount of attention documenting how those poor souls left in the city -- who are certainly some of the poorest people in the United States -- are "looting" stores.

Point 1: everything in that city is water-logged trash, and no insurance company in the world is going to pick among the, say, sneakers from a Payless Shoe Source that is currently under 8 feet of water to figure out which are salvageable. Hint: nothing is salvageable.

Point 2: In the worst natural disaster to strike this continent within recent memory, America is so fucked up on the race issue that it's still all we can think about. Check these links out: (thanks to Adam Lipscomb)

Caption (emphasis added): A young man walks through chest deep flood water after looting a grocery store in New Orleans on Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005. Flood waters continue to rise in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina did extensive damage when it made landfall on Monday.

Caption (emphasis added): Two residents wade through chest-deep water after finding bread and soda from a local grocery store after Hurricane Katrina came through the area in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Black people loot. White people find stuff. Go puke your guts out now.

Point 3: They have no food, no water, most of the clothes are destroyed, and they're battling for survival. The news today mentions stories of armed police called in to stop people from "looting" grocery stores. Need I remind you THAT THEY'RE LIVING IN A GODDAMN SWAMP THAT USED TO BE THE 35TH LARGEST CITY IN THE WHOLE COUNTRY? Christ almighty. Let them take what they fucking need.

Well, whatever you do, give a little money to Red Cross.

Here's a few more pictures that I find awe-inspiring.

From Pascagoula, MS (looks like an outtake from Fitzcarraldo, no?):

Biloxi, MS:

I-10 near Slidell, LA:

Dauphin Island, AL:

Bayou La Batre, AL:

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

I can't say this better than the brilliant Leonard Pierce on his LiveJournal:

Hey, writer-types, professional and otherwise!

We’re getting the band back together. That is, the editorial staff of the High Hat (of which I am privileged to be a part) is putting out a new issue. Issue #6, this will be, and if I have anything to say about it, it’ll be the boss jock issue of all time.

The High Hat, and if you don’t know ya betta ax somebody, is the best goddamn cultural studies/criticism ‘zine on the whole fuckin’ world wide web. It’s put out five issues since its inception in 2003, and they’ve been so good that if they were in paper format, you’d pay a hundred bucks for each one of them and be happy to do it please sir may I have another. Well, yes! You may! And at the low low cost of free.

What we need to make the next one even better is your help. If you’re interested in writing for the next issue of the High Hat, drop me a line (highhatmagazine at hotmail dot com) or post in comments – but only if you’re serious. We won’t take everything submitted, and even though we can’t pay you, we demand quality pieces, turned in on time, from people who really care about what they’re writing. From us you’ll get effusive praise, a deft editorial hand, and a well-read, swanky credit for your port-folio; from you we want sharp, insightful, funny (or dead serious) criticism, great prose, the best you got. This is for the love of the game, kids. If you haven’t read the Hat before, take a look, and if the excellent articles we’ve done in the past don’t convince you this is something you wanna be a part of, nothing will.

Deadline for application is Sept. 9th. Deadline for your completed piece is Sept. 30. Projected publication date is mid-October. Here’s what we need:

DETRITUS – the junk drawer. This is where the uncategorizable stuff goes: politics, general culture studies, games, technology, rants and raves.

MARGINALIA – our books section. Book reviews, literary criticism or theory, retrospectives on authors or genres, comics writing, state-of-fiction, whatever you got about the world on the page.

NITRATE -- film and video. Movie criticism, interviews with filmmakers, trends in cinema, video, stage and screen. If it moves, write about it.

POPS & CLICKS – our music section and general raison d’etre. Classical, rock, hip-hop, experimental, jazz, and everything before and after. Criticism, essays, laments, obituaries.

POTLATCH – every issue, we have a special themed section where we talk about one general subject or idea; in the past we’ve done potlatch pieces on Sam Peckinpah, our yearly Top Tens, democracy in popular culture, labor issues, and people who died. This time around, it’s “The Academy of the Underrated” – cultural artifacts, phenomena and trends that our writers think are criminally underappreciated by the critical consensus. Got an idea along these lines? Wanna write a piece about it? Hit us up.

STATIC – television, the drug of the nation, all hail grand pixelator. If it’s on the small screen, we wanna cover it: TV series, minis, foreign television, DVDs, anything. Smart writing wanted.

That’s it! Length is negotiable; should be at least a thousand words, though, and probably fewer than 50,000. Pay is non-negotiable: it will be zero. If you’re interested, send me your pitches in comments or via e-mail and I’ll run them past the other editors and let you know ASAP if you’re in. Thanks to everyone who wants to be part of this, and especially to everyone who already has.

(ETA: We're not just looking for writing! If you've got art, photographs, recordings, or anything else that seems relevant to the High Hat's outlook, by all means, we'd love to consider it. Note that we aren't looking for fiction or poetry, but we do occasionally run comics, games, and the like, as well as our usual essays, criticism, cult-stud and memoirish stuff.)

Monday, August 29, 2005

Jandek at the Scottish Rite Theatre, Austin TX, August 28, 2005.

Two drummers, one of whom was avant-jazz guy Chris Cogburn, and the other of whom looked 17. A young-looking bassist, too. And the man, the legend, the weirdo from all those album covers: Jandek.

Some of you may wonder: does Jandek tune his guitar? After tonight, I can say definitively that the answer is yes. Jandek does, in fact, know when his guitar is out of that god-forsaken tuning he loves so well and actually adjusted his B-string from somewhere south of plong to somewhere in the vacinity of doink.

He played for an hour and a half on the nose. After the last song, he held his guitar briefly, as if considering playing another song, then abruptly took the guitar off, put it in a case, and walked off stage.

Some of you may wonder: is Jandek a tech geek? After tonight, I can say definitively no. At one point, he accidentally hit the pickup configuration switch, changing his tone drastically, which confused him for several seconds before he decided that the new tone was a-ok with him.

This was easily the geekiest rock crowd I've ever seen. Outside, we looked like we were waiting in line for free 20-sided dice. The show was in the Scottish Rite Theatre, and we wondered through several ornate rooms, full of portraits of grumpy old men before reaching the theater. I half-suspected that we were being inducted into a fraudulent age-old conspiracy.

Some of you may wonder: does Jandek play guitar solos? After tonight, I can say definitively maybe, given a loose definition of "solo." Several times, Jandek played little picked leads that seemed as random as his chords. He seemed pleased with himself, and once even broke out into a Jandek-sized smile (i.e. tiny and secret).

What else? With two drummers, Jandek rocked the joint occasionally, stirring up music as loud and aggressive as any free jazz I've witnessed. He mostly watched the 17-yr-old drummer and the bassist, who looked to be in his early 20s, maybe. I suspect that they might be in the youth group in Jandek's apocalyptic cult. Or, as my friend suggested, perhaps they're his wards, like Robin. Jandek does have a rather Batmanish persona.

Chris Cogburn was doing the most interesting things on stage - sometimes getting high squawky noises by turning a cymbal sideways and running it up and down his drums, sometimes doing the avant-jazz standby of the superfast run through all the cymbals, changing drumsticks along the way - but it was hard to take your eyes off of Jandek. He exuded a strange blank menace, never looking at the audience at all, but somehow giving off a vibe somewhere between cult leader and serial killer. His lyrics were surprisingly trite at times, although quite a few of them had the creepy-but-beautiful old Jandek charm.

He occasionally fretted with his thumb. I mean, not just the low E, but all the way across, like Thurston Moore with a drumstick. Oh, I heard someone say that Thurston Moore was there, but I didn't see him (this has turned out to be a mishearing - what my friend said was that Thurston Moore should be there). One of the guys two rows up from me was in Jandek On Corwood, but it wasn't Douglas Wolk or Gary Pig Gold, so I don't know this guy's name.

There was a Jandek VIP section in front of us. In a more perfect world, it would have been filled with people no one had ever seen or heard of before. In this world, it was mostly filled with SXSW honchos.

Some of you may wonder: is an hour and a half of live Jandek exhausting? After tonight, I can say definitively that the answer is an unqualified yes.

Update: Joe Gross has his take on it here. Joe (who had the vantage point of sitting directly to my right) refers to the giant shadow and the introduction that I forgot to mention.

New update! The second drummer was Nick Hennies, who will be 26 in a couple of days. No word on the veracity of completely unsubstantiated rumor (created above and repeated nowhere else!) that he might be a member of Jandek's apocalyptic cult or, possibly, Jandek's young ward. Perhaps because they are stupid rumors!

Book No. 25: The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton

I'd heard quite a bit about this book over the years, and rightfully so. It's witty as hell, full of surprising twists and turns, and ultimately a mystery in the medieval sense of the word.

In short: Gabriel Syme, a poet who is also a policeman, infiltrates the Central European Council of Anarchists (didn't I mention it's a witty novel?) as Thursday, one of seven leaders code-named by the days of the week. The head of the council is Sunday, an immense man who terrifies the others. One by one, Syme discovers that none of the other men are who they seem to be, and, in the end, chases Sunday straight out of the spy novel of the first 80% of the book into pure allegorical fantasy writing.

Although I believe that Chesterton was on the opposite end of the political spectrum from my own sympathies (which, given the century between us, means squat), The Man Who Was Thursday has an ambiguous moral that appeals to and intrigues me. Smarter men than I have delved into the meanings with (one supposes) more preparation than I have had, so I'm just going to stick with the simple note that I liked it and am glad I've read it. I note that most of the recommendations for this book on the web appear to be from sci-fi and Catholic readers; however, I stand as proof that the book (well, novella, really) also appeals to liberal, highfalutin'-lit-loving humanists.